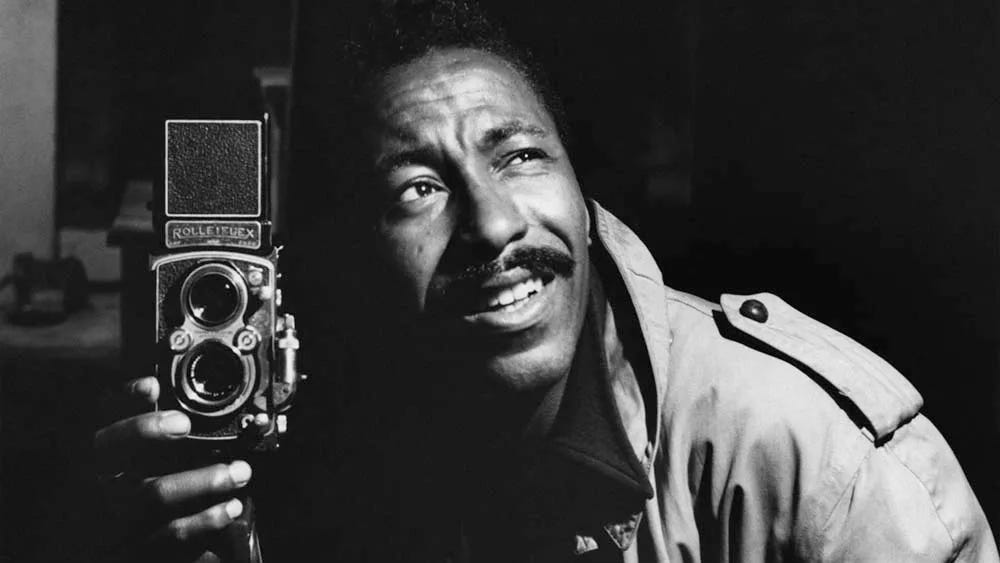

In 2015, I encountered Gordon Parks' powerful photography at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, and I was blown away. The story of his journey as a humanitarian and social justice advocate is special to me for a few reasons beginning with the fact that he learned photography without formal training—no textbooks, no YouTube tutorials, no mentors. Just true grit and a love for the arts.

In 1912, Parks was born in Fort Scott, Kansas, as the youngest of 15 children. To say he had a tough childhood is an understatement. His mother died when he was just 15. His father was often absent and they were dirt poor. Parks’ love for music and the arts pulled him through.

He bought a pawnshop camera—a Voigtländer Brilliant, for $12.50. Of that purchase, he once said, “I bought what was to become my weapon against poverty and racism.” Through self teaching, he began earning photography jobs and eventually solo exhibitions.

His first big professional break was when Roy Stryker of the FSA (Farm Security Administration) took Parks on as an apprentice. Stryker had already hired renowned photographers like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans and he hesitated to hire Parks because of his race. Yet, after some coaxing from another photographer and after reviewing his work, Stryker was impressed enough to give him a chance.

Parks was eager to document the African American community but did not yet realize the challenges he would face as a Black man in the city. FSA director Roy Stryker suggested that Parks begin by exploring Washington without his camera, knowing well what would happen.

Parks found bigotry everywhere. He was turned away by restaurants, kicked out of theaters, and denied service at a respected department store where he attempted to buy a winter coat. After just a few days, Parks was utterly demoralized by the rampant racism.

When a humiliated Parks returned to FSA headquarters, Stryker recommended that he focus on documenting not the actions of the oppressor, but the stories of the oppressed, bringing his project closer to home, looking for subjects and storylines.

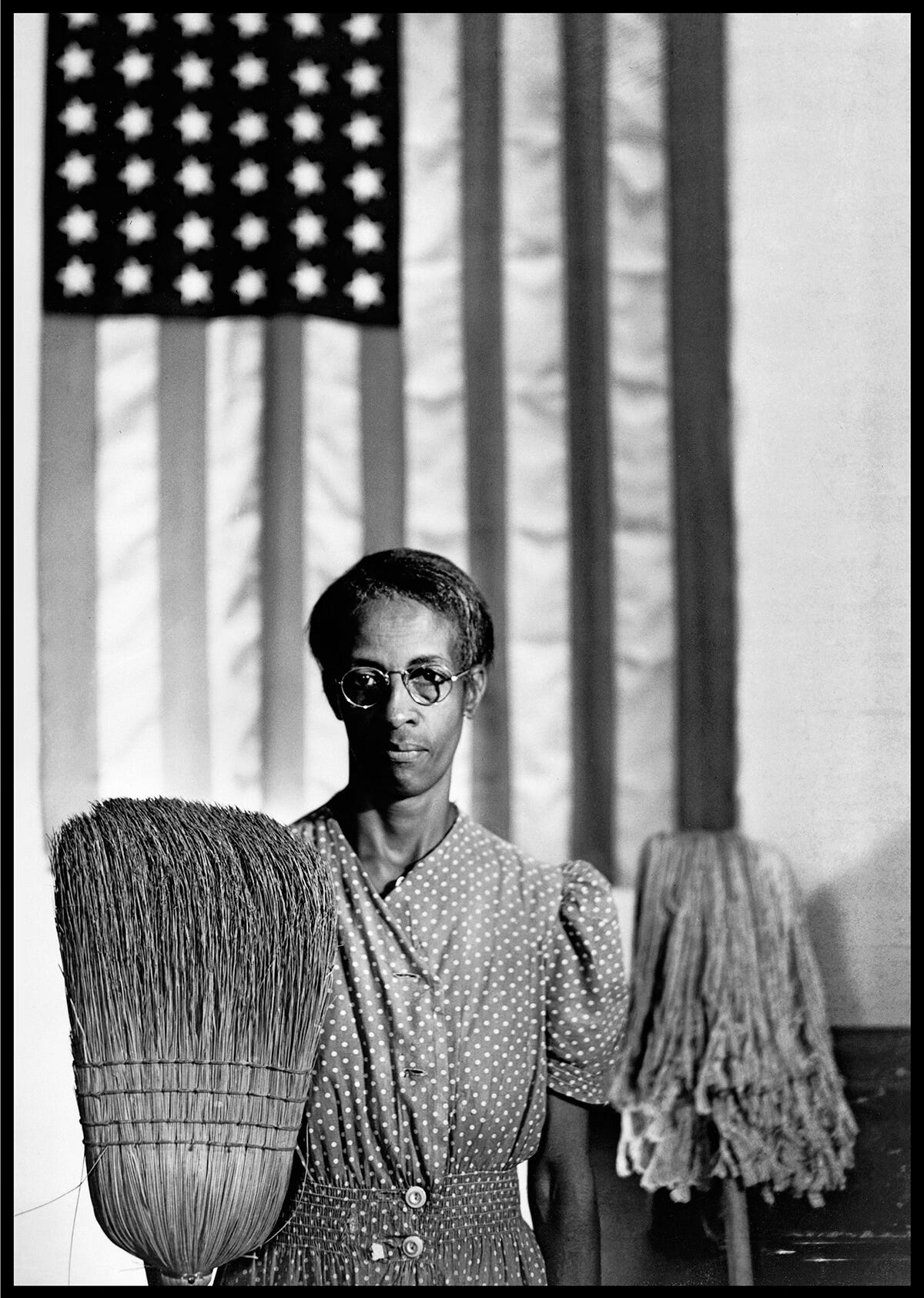

Parks approached a Black woman who was cleaning the FSA offices. Her name was Ella Watson. She told Parks she had become pregnant out of high school, and that her husband had been shot to death two days before their second daughter was born. She was now working to support herself and her two grandchildren. At the end of their conversation, Parks asked if he could take Watson’s picture. She agreed, and for four months gave him access to her home and her community. The resulting photographs were a breakthrough in Parks’ career.

When Parks showed "American Gothic" to FSA head Roy Stryker, he was warned that it could cost them their jobs. Since the FSA was a government agency, the image was considered too controversial. Despite being taken in 1942, the photo remained unpublished until 1948, after Parks became the first Black staff photographer at LIFE magazine.

“At first, I asked her about her life, what it was like, and so disastrous that I felt that I must photograph this woman in a way that would make me feel or make the public feel about what Washington D.C., was in 1942. So I put her before the American flag with a broom in one hand and a mop in another. And I said, "American Gothic"—that's how I felt at the moment. I didn't care about what anybody else felt. That's what I felt about America and Ella Watson's position inside America.”

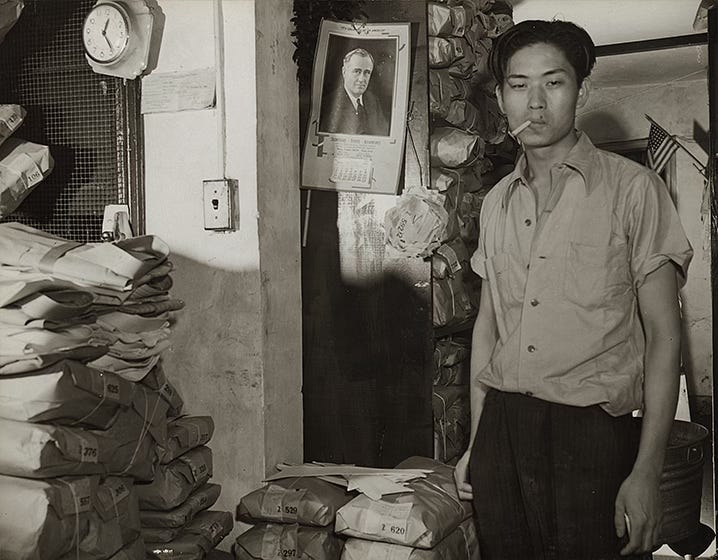

As the caption indicates below, Parks took this photograph as part of his work documenting Ella Watson’s life. It offers a glimpse of the diversity of people who contributed to the labor force in and around Washington, DC.

Notice that the subject is flanked by a picture of 32nd President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and an American flag.

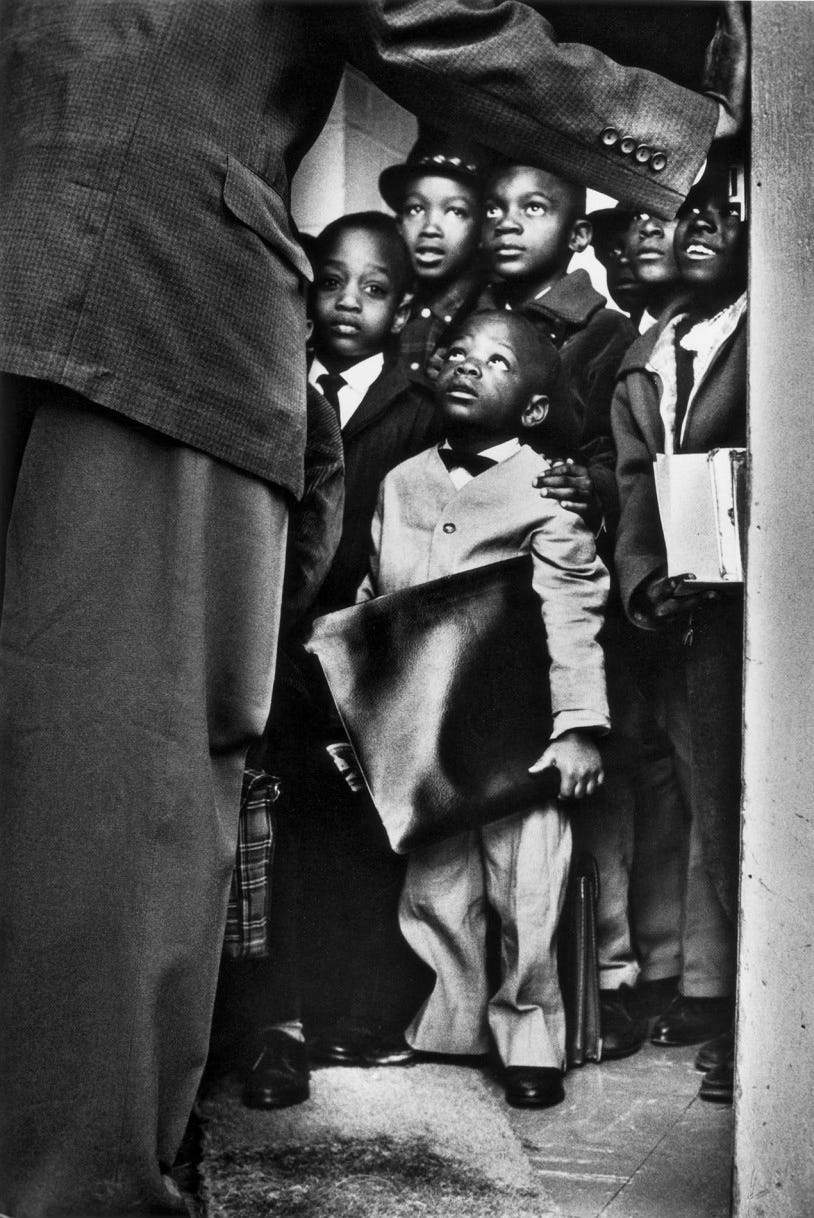

LIFE Magazine sent Parks back to his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, to track down members of his segregated junior high school class where he attended his first 16 years in small, segregated schools. His resulting photo essay was slated to appear in Life in the spring of 1951, but was ultimately never published. The book Back to Fort Scott is the 80-photo series in a single volume. There’s a comprehensive video from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts that goes into detail about this and other aspects of that timeframe in Park’s life.

Parks also wrote about his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, in his autobiographical novel and subsequent film, The Learning Tree, which was among the 25 films placed on the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1989. He went on to direct other films, to author several books, and to write original musical compositions, film scores, and a ballet.

He once told an interviewer that he could not simply photograph the person who had discriminated against him, "and say, 'This is a bigot,' because bigots have a way of looking just like everybody else. What the camera had to do was expose the evils of racism, the evils of poverty, the discrimination and the bigotry, by showing the people who suffered most under it."

One exhibit I wish I could have seen: I, too, am America exhibit. The title of the exhibition comes from a line in the 1926 poem I, Too by Parks’ friend Langston Hughes. The poem captures the mixed emotions of justified hurt, as well as self-assured pride and hope felt by a Black child in America.

“I am the darker brother. / They send me to eat in the kitchen /When company comes” before envisioning a time when “They’ll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed— / I, too, am America.” In his opening of a 1968 essay about the life of the Fontenelle family in Harlem, Parks repeated the line as he also expressed a mix of rage and hope: “I am you, staring back from a mirror of poverty and despair, of revolt and freedom. ...There is something about both of us that goes deeper than blood or black and white. It is our common search for a better life, a better world. …My children’s needs are the same as your children’s. I too am America.”

Parks also made significant contributions to the world of film and literature. In 1971, he became the first African American to direct a major Hollywood film with Shaft, a groundbreaking action film that was a huge success. Parks also received the National Medal of Arts in 1988 and has received over fifty honorary doctorates.

His career took him from the chronicling the Civil Rights movement for two decades—and the harsh realities of segregation—to a lifetime of artistic achievement, captured both in still photography and motion pictures. Though Gordon Parks passed away on March 7, 2006, at the age of 93, his work and influence will continue to inspire and resonate for years to come.

Just got his book for Xmas. His work in Harlem during the height of Black Panthers is stunning.

Great story, beautifully written. Kudos. I'lll confess, I did not know of Gordon's work untill recently, he does not get nearly enough recognition as some of his peers do.